INDIGENOUS INHABITANTS OF THE HUNTER RIVER ISLANDS

By Cherylanne Bailey

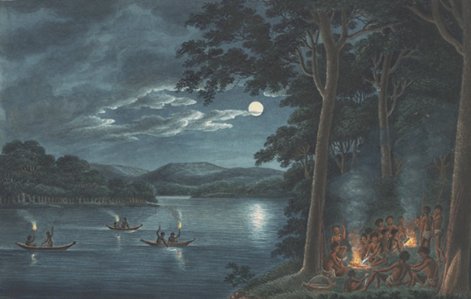

Photograph:- Joseph Lycett, Fishing by Torchlight, Other Aborigines beside Camp Fires cooking Fish, nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an2962715-s8

Aboriginals camped on the riverbank of the Hunter River for thousands of years until approximately 1860 when their traditional way of life was interrupted and overwhelmed by European settlement. The Aboriginals must have regarded the Island as a paradise with the river teeming with aquatic life and the land rich with game. From many accounts it appears that both the nomadic Awabakal and the nearby Worimi Tribes used Ash Island as literally a supermarket thoroughfare where they stopped when going from place to place to replenish their supplies, harvesting available food sources on their journey up and down the river and west to Sugarloaf across the Hexham Swamp. According to an article contributed to the Stockton Historical Society by Vera Deacon, Platt’s Channel:A Story of People, Maps, Memories or An Historical Row Along the Hunter’s South Arm, whilst she was unable to locate any Aboriginal names for the Islands, John Warner’s 1833 Blanket Distribution Return and Reverend Threlkeld’s 1836 Return, record Wallungull as the chief of the Ash Island clan or tribe.

Comments by a Towns of Dempsey Island descendant include that a fewAborigines still lived on Mosquito Island in the 1860s and “Grandma Towns administered first aid to some who lived on Dempsey Island in the 1920’s.”In August 1893, a Newcastle Morning Herald account reads that around Ash and Dempsey Islands a reserve of 100 feet was gazetted so the indigenous could live on the Island and fish and prawn in the mangroves. Despite not locating the Gazette Proclamation the Schoolmaster’s House has several old maps which clearly define this Aboriginal Reserve.

1828 Census

The 1828 Census records the total indigenous population as 260. Newcastle: Coal River Tribe — 50 men 40 women 50 children and Ash Island Tribe — 40 men 35 women 45 children.

John Maynard presents a pre-1788 insight into Aboriginal communities in his Callaghan: The University of Newcastle’s Whose Traditional Land? as follows:

“The Pambalong, like all of the Aboriginal clans, lived in a virtual paradise of plenty. They had the added rich resources of the swamp and wetland areas within their clan territory. Their already rich diet of the marine and marsupial variety was supplemented with mud crabs, wild duck, waterfowl and an endless variety of other birdlife.”

Quoting from Edward James Sparke’s “A Remarkably Fine Place”:

“Pre-European settlement, the farmland was inhabited by the Indigenous Pambalong clan, their country known as Barrahineban. This stretched from current Newcastle West along the fight bank (southern side) of the Hunter River, then west through Upper Hexham (Tarro) to Buttai, and across the foothills of the Sugarloaf Range to the northern tip of Lake Macquarie and back to Newcastle West.”

Mrs Elizabeth Muncaster was interviewed by the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate on 22 November 1933, the day following her husband John’s funeral, when she stated she was a native of Brush Grove Parramatta and went to Moscheto (Mosquito) Island aged five years, later settling with her family on Dempsey Island which was at that time “inhabited by Blacks”.

She married John Muncaster, he having emigrated from England as an employee of her father Richard Bell. After marriage, the couple took up dairying on Dempsey Island which they continued until his death 47 years later.

With a keen memory, she advised she could recollect may interesting stories about life on Dempsey Island as far back as the 1850s when indigenous were employed in the husking of corn. She recalled that many of the natives lived on the Island and others living at North Shore (Stockton) would paddle across in canoes to visit.

“Aborigines and Ash Island”

By Beatrice Brooks

1803 Aborigines and Ash Island “Living on the islands of the Hunter estuary were Aborigines belonging to two tribes, the Awabakal or Lake Macquarie tribe and the Worrimi or Port Stephens tribe. The river is usually regarded as the dividing line but it is likely that all Aborigines of this area were interrelated.”

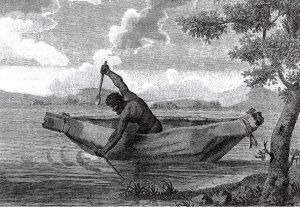

In 1801, an exploration party led by Lieutenant-Governor Colonel Paterson landed on the Hunter estuary islands where they made several sightings of Aborigines. “He reported that, on the 19th June 1801, the party returned to Ash Island and saw some natives at a distance… On another occasion, the explorers tried to approach a family group but they fled. “We came to a spot which they had just quitted, and observed the marks of children’s feet. The ground was covered with the shells of fresh water fish, of the sort found in the rivers of England and Scotland and called the horse mussel… On many occasions the Aborigines were seen in bark canoes which they used with great skill, even managing a small fire on a hearth stone in the bottom of the vessel so that cooking could proceed while fishing continued. They also used weirs to trap fish in the waterways around the estuary islands.””

The Reverend Lancelot Edward Threlkeld was known as a friend of the Aborigines and conducted a mission among the Awabakal Tribe at Lake Macquarie. Included in his records are also references to Ash Island clan members of the Awabakal. He mentioned in 1833 an elder named Wallungull, and in 1836, Muntorin a male of about 38 also two children Takkun and Toti their ages about nine and seven.

Early in 1854, The Maitland Mercury reported the accidental death of the Awabakal Aborigine Harry Brown. Sadly, the Mercury thought him to be the last full blood Aborigine of this area. It also reported that Harry Brown would frequently take white people fishing and hunting along the Hunter River. (All the above from John Turner, Folder 5 An Aboriginal Perspective 900/FOL/5)

Harry Brown and another Aborigine, Charlie Fisher, had travelled with the explorer Ludwig Leichardt on the two occasions of Leichardt’s successful expeditions. Leichardt credited the Aborigines with the expedition’s safe arrival at Port Essington. That they were alive and had made it to their destination was, he said, solely from the aid of the Aboriginal hunting and survival skills. Brown did not accompany Leichardt on his third and fatal expedition in 1848. This expedition had intended to travel from Brisbane to Perth but never arrived at their destination. Brown was a member of the search party which attempted to find Leichardt in 1852.

Rev. Threlkeld wrote a newspaper article in which he considered that both Ludwig Leichardt and Harry Brown would still be alive if Brown had accompanied the explorer on that last expedition.

In 1801 accompanying Colonel Paterson’s expedition to the Hunter was a Lieutenant James Grant who at the time visited Ash Island and wrote an account of this visit, which included observations about the island’s Aboriginal inhabitants. He describes the gift of a tomahawk to an Aborigine and a demonstration of its use “The crew of the boat, in which he [the Aborigine] was conveyed on shore, wishing to have proof of his dexterity in the use of his new acquisition, pointed to a tree, as if they wished to see him climb it. He readily understood them, and making a notch in the tree with his instrument, placed his foot into it, continuing the same practice; thus he very nimbly ascended to the top, though, the tree was of great thickness, and without branches that could assist him in the ascent to the height of forty feet [12 metres]. From this tree, he removed to another, by which he descended…. The natives have hatchets of their own, formed with sharp stones, and which they used for the same purpose, and I have indeed remarked that many of the trees are notched.” (Lieutenant Grant’s “Voyage of Discovery…” The section covering the exploration of the Hunter River is held in the Ash Island library 900/GRA)

Although Lieutenant Grant admired the physical capabilities of the Aborigines, his belief in their mental capacity was far from complimentary. Whereas Rev. Threlkeld described the Aborigines “as possessing a good capacity, and by no means the degraded, intellectual beings they have been represented.”

In March 1827, the Colonial Secretary directed a count to be taken of Aborigines. The count for the group known as The Ash Island Tribe consisted of 120 persons. It was the intention of the Governor of New South Wales to issue “blankets and slops to the Black Natives on the 23rd of next month in commemoration of His Majesty’s birthday” The Ash Island Tribe accounted for nearly half the numbers of Aborigines recorded in the Newcastle district at that time as the following table shows

Coal River Tribe:- Men 50 Women 40 Children 50 Total 140

Ash Island Tribe:- Men 40 Women 35 Children 45 Total 130

In 1833, another muster of Aboriginal persons in the Newcastle District as part of the “Blanket returns 1833” noted the Ash Island Tribe and the Pambalong Tribe. (Newcastle Aboriginal Communities Snapshot Profile 2006)

Aborigines who lived on the estuary before the Hunter River Valley was “opened up” had a very stable hunter-gather lifestyle, Foods of all types meat, plant food, honey and in particular, fish and shellfish were plentiful. What made the area attractive to them also made it highly desirable for white settlers. Following the commencement of white settlement, the Aborigines were squeezed out of their home territories and became fringe dwellers. They were also exposed to deseases for which they had no immunity. As well as losing access to traditional food sources, this upheaval was responsible for the loss to them of those important social links to their way of life, which were so essential to their behaviours and beliefs. “Sadly, the rhythm of this culture was interrupted by intruders who did not understand and did not respect a way of life so different from their own.” The Hunter Aborigines suffered badly at the hands of the early white settlers. John Turner believed ill-treatment of the Aborigines had started with the earliest timber-getters that is prior to 1801.

Richard Windeyer (1806-1847), was a barrister, a member of the NSW Parliament, and the owner of nearby Tomago House. He was once described by a newspaper as “That indefatigable friend of the Aborigines”. He was a member of the Aborigines Protection Society and appeared as a prosecutor in the trials following the Myall Creek massacre. He took up the cause of the fast dwindling Aborigines and helped organize a committee to enquire into their worsening state. He worked to defend them in court and to try to secure money for medical treatment for them. He did this “not indeed in the hope of effecting much good, but because they were so utterly friendless and helpless, that it was inhuman to pass them by in silence.”

Boris Sokoloff in 1973 described Aboriginal culture pre-European and also shows how European settlement disastrously affected their traditional way of life. One aspect of European culture where Aboriginals flourished however was on the sporting field. Where ‘they showed their prowess in sports and were much admired by the Europeans”. (B. Sokoloff, The Worrimi: Hunter Gatherers…. 1973. 900/SOK)

John Di Gravio tells of a local Aboriginal Dreaming Story of the Hunter River and Nobbys Island. This story belonged to the Awabakal’s Newcastle tribe (Muloobinba). The story centred on the belief that it was the abode of an immensely large Kangaroo that offended kinship laws. There is also a great traditional story there of how coal was made. (From the website Nobbys Coal River Heritage Park, a printout of these two stories is in Folder 5, 900/FOL/5)

In 1995 in the book 131 Radar Ash Island there is a chapter “Some notes on Ash Island” by Jack Fraser that tell us Ash Island was the home of “the Garuargal tribe of Aborigines.” There is an historical map showing Aboriginal names which supports this. A copy of this map is kept in the Historical Maps folder.

One of the Kooragang Wetland Rehabilitation Project restoration objectives is to protect Aboriginal heritage values. ”The CMA [Hunter-Central Rivers Catchment Management Authority], in partnership with the Awabakal and Worrimi LALC [Local Aboriginal Land Council] are embarking on the development of an Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Management Plan for KWRP, which will further integrate both traditional and contemporary Aboriginal culture with the project’s objectives.” (P. Svoboda)

“Mur-rang Korung” is from the local Kittang language and mean “Beautiful wilderness”. It is the name given to an area west of the radar bunkers where two hectares of land have been dedicated to planting with those plants chosen in consultation with local Aboriginal groups. “Until recently most of our knowledge of the plants that once grew on the islands of the Hunter River Estuary has come from historical records left by early European settlers such as Helena Scott and the naturalists and explorers, Ludwig Leichardt and John and Elizabeth Gould. However plantings based only on records from European settlers lack the perspective of the original inhabitants.” By consulting with local Aboriginal groups and organizations, a species list was developed and we obtained the traditional names of these plants. Plants chosen are those of the local areas and have traditional significance. These were used as a food to supplement their mainly seafood diet, or as a source for medicines, some were poisons for stunning fish, and others were the materials for the many useful items such as twine, bark for vessels etc. The pathways through this area also have significance and are representative of the snakes of the Dream Time.

On July 25th 2003, the official launch of Mur-rang Korung was held. In conjunction with the local Aboriginal representatives, indigenous and non-indigenous schoolchildren started the planting of the new forest with about 500 trees. This was followed by a traditional ‘’welcome to country” by the Worrimi. In addition, there was a “welcome dance” performed by the dance group Girrawaa Yarruudanginya and this was seen as a feature of the day. Later more plants were added to this area by others making a total of 15 thousand. (KWRP Media documents 2003)

In 2008, the Kooragang Project celebrated its 15th birthday. At the celebrations held on the island, there was a traditional ‘Welcome to Country’ by Aunty Sandra Griffin. On that day, she made mention of living on the island and she spoke of the times when they, the Aborigines, wished to venture from the island. They did not use the Ash Island Bridge at the western end of the island. Instead, they crossed the river by walking along the water pipe and returning the same way. Not only the Aborigines used this route, and there was many a young lady dressed in her Saturday night finery who also walked the pipeline instead of crossing via the bridge.

Ray Peterson, of Beresfield, once a resident of Ash Island, remembers an Aborigine who used to work for his grandfather on the islands. This Aboriginal man, Bill Ridgeway, was quite a large man with very big hands. Mr. Peterson recalls that Mr. Ridgeway’s hand span was so large that he was able to pick up a kerosene tin by simply clutching the top of the tin with the fingertips of one hand. He was also a well-known cricketer and would very successfully wicket keep for his team without the aid of gloves and it was a ‘comfort’ to bowlers to see the imposing figure of Mr. Ridgeway behind the batsman. Because of his ability to stop anything the bowler sent down that passed the batsman.

Vera Deacon, who has lived on both Mosquito and Dempsey Islands, told us “So far I have uncovered very little about the Aboriginal inhabitants. We knew only one. He was very old” his name was Moses, a friend of her father. Moses befriended them when her family went to live on the Islands. They ‘fished the river and cut oyster sticks” together. She recalls that Moses was a very good mechanic and was adept at making many other useful things such as fishing nets and such. In fact, he could just about set his hand at anything, showed Vera’s father where to fish, and helping him in many other ways. At one time when the propeller of her father’s boat broke Moses carved a new one for him from island timber to use as a stopgap.

(Vera also says there is a map showing a 100 feet wide reservation on Ash Island “for the Aborigines to support their fishing.” So far have found a map showing a 100’ strip but this map just says reserved. But I also found an unsourced comment “Unlike other islands the government reserved an area from ‘high water mark all around the island the reason given in the old gazette being that the Aborigines could live on the island, and have access to its shores. At that time Ash Island was a favoured spot with the blacks, and although the reservation still exists, the people, for whose benefit it was proclaimed have long since disappeared from the face of the earth… Date written in pencil is August 4, 1893.”)

Visitors to the island might also be interested in the lovely sculptured tree carved by the artist, Worrimi Dates, at the Hunter Region Botanic Gardens on the Pacific Highway at Heatherbrae. It is a Red Ash, the Alphitonia excelsia, which had died and instead of removing the tree, it has been turned into this wonderful sculpture. It includes animals, birds, and such. At the Botanic Gardens, there is a magnificent example of a living Red Ash, which can seen as one walks from the car park to the visitor’s centre.

Red Ash is also a native to Ash Island and is again growing here, although the island itself is actually named after another Ash tree called Elaeocarpus obovatus. Since the start of the Ash Island Revegetation Program there has been almost a thousand Red Ash trees planted here. As previously mentioned the Project has been gathering the Aboriginal names for those plants indigenous to the island. For example an Aboriginal name for the Red Ash is ”Coraming” it has strong medicinal properties and with correct preparations may be used as a medicine and also as a liniment. The Dianella which grows just outside the cottage is known as “Paroo” it is a food source and as well the leaves are useful to make twine. A word given for tomahawk, back in the early part of the 19th century, by the Ash Island Aborigines, was ‘Mogo’

A study by GHD on behalf of the Tomago Trunkmain Upgrade on Ash Island which is being undertaken by the construction firm Diona, found no Aboriginal sites such as shell middens, scarred trees, artifact scatters, axe grooves or burial sites recorded in this area of Ash Island. Another Environmental Assessment identifies two Aboriginal sites on the whole of Kooragang Island. One site being near the Tourle St. Bridge and the other site on the eastern end of Moscheto Island In all there is knowledge of some 63 recorded archaeological Aboriginal sites within an area in and around Kooragang Island of 14 kilometres (East-West) by 8 kilometres (north-South). (Environmental Assessment by Umwelt on behalf of Manildra Park Pty. Ltd. for a Marine Fuel Storage/Distribution and Biodiesel Production Facility on Kooragang Island, January 2008)

A third assessment undertaken to look for Aboriginal signs of occupation on Kooragang Island likewise found little evidence. It was their opinion archaeological evidence may be found beneath the landfill on the eastern parts of Kooragang Island and gave recommendations for investigating this when able to do so. They found the timber cutters would mostly have removed canoe trees and scar trees and any such trees still remaining would have been removed when settlers cleared the land. They inform us that Aborigines have lived in the Hunter Region for at least 17 000 years but that the islands are of a much younger age. “The Hunter River islands (now collectively Kooragang Island) are … features that have been formed in delta-like conditions since the Holocene high-stand of approximately 5 000 years ago.” (Aboriginal Heritage Assessment of Bulk Fuels Storage Facility Kooragang Island NSW by HLA-Envirosciences 2007 CD658/HLA)

In the summing up of this Assessment HLA explained, “As a whole, it can be concluded that the Aboriginal population of the Kooragang Island region prior to colonial settlement were an intelligent and resourceful people”. That the “composition of flora and fauna species present are indicative that there were sufficient resources to support a moderate size population of hunters and gatherers”. Lastly, “Although historical discrepancies arise over the traditional boundaries it is understood by both the Awabakal and Worimi people that the individual islands (where Kooragang Island now stands) were a meeting place for the two tribal groups. It is here that trade of knowledge and goods would have been conducted, ceremonies undertaken and family matters (i.e. potential marriages) discussed.”

Aborigines were still on the islands when the Scott’s were here 1836 (Threlkeld), possibly the 1850’s (Harry Brown) and then there is also information from the 1920’s, through to the 1950’s. But in between? Of sad thought is this also from John Turner “Thomas Fennell, a newly arrived Englishman, wrote in 1847 to reassure his anxious mother. I have not seen any natives in their wild state: there are none left in these parts, we have nothing to fear but the snake, the scorpions and a species of spider ….”

In the Aboriginal Folder there is mention of Lt. William Sacheverell Coke of HM 39th regiment at this time 1827 he was second-in-command of the convict station at Newcastle. During his appointment to Newcastle he describes his contacts among the aborigines of this district . His main recreations of fishing, shooting and stuffing specimens, brought him into contact with several Aboriginal men whose company he obviously enjoyed.”

He attended a number of hunting and fishing expeditions with several different Awabakal Aborigines who he names. There were other occasions where the Aborigines have gone without him and he entrusted them with his firearms. His diary entries from the 3rd of February show there were occasions when the Aborigines having gone shooting without him frequently returned with kangaroos and such. Another time he writes “6th July Went out Shooting took Joney a black with me. On our return Parmegony had arrived, but he brought only two black Ducks, his Shot being by far too small to kill the Large Kangaroos.” “

7th July Sent Parmegony to Ash Island – he returned with two immense Hawks only, fine sport for him as they are a delicious morsel.” When he returned to Sydney his diary entry read “20 Sept. Sailed for Sydney. Savage life undoubtedly preferable to civilized”. (Beatrice Brooks 2009)

“Newcastle Region Art Gallery has recently acquired two very significant watercolours by Richard Brown painted in 1820. Depicting Burgun and Coola-benn, two important indigenous leaders from the Hunter.” Ron Ramsay, Director Newcastle Region Art Gallery.

Coola-benn we are told was a chief of Ash Island but as yet there is no other information available. We do not yet know if he is a member the Awabakal or Worrimi. Richard Brown was a convict artist who spent time at Newcastle. As well as the Aboriginal paintings Lieutenant Thomas Skottowe had him paint local flora and fauna. [B.B.2011]